Posted on 02/12/2019

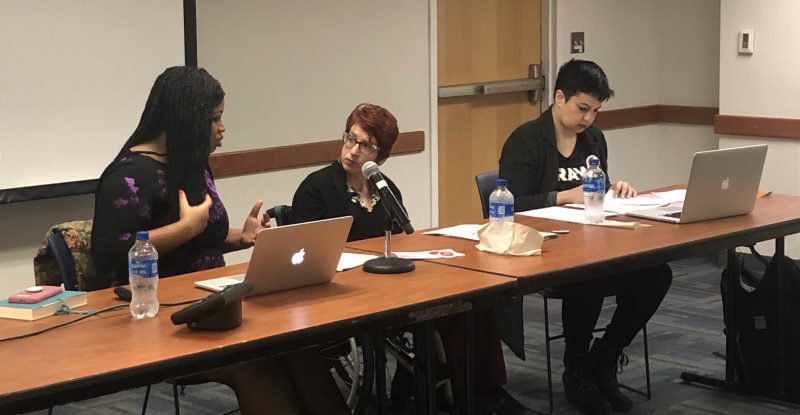

The Women’s and Gender Studies Program would like to thank everyone who attended our panel on “Feminism and Incarceration.” Approximately 80 people came to hear esteemed panelists Dr. Khalilah Brown-Dean (Quinnipiac University), Dr. Liat Ben-Moshe (University of Illinois, Chicago), and Dr. Lena Palacios (University of Minnesota).

As Dr. Brown-Dean astutely explained, the United States leads the world in mass incarceration. For every 100,000 people in the United States, 723 are currently incarcerated. To place this figure into perspective, the world-wide average is 100 people incarcerated per 100,000 residents

Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities within the prison system have not been adequately addressed. A disproportionate percentage of the prison population are women, particularly women of color and Latinas. The number of incarcerated women has risen 850% since the 1980s.

Dr. Brown-Dean highlighted a disturbing correlation between the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the civil rights movement, and an alarming increase in the imprisonment of people of color. The increase in incarceration was not accompanied by a rise in crime. Instead, Brown-Dean explains, the increase is political—a direct result of policy change.

The incarceration of women has had a devastating impact that goes far beyond those incarcerated. 60% of women in prison are the custodial parents of minor children, many of whom are now relegated to the foster care system, leaving them more likely to develop anger issues and learning disabilities. Brown-Dean notes that the school-to-prison pipeline and mass incarceration are interlocking systems. She challenges the notion of private prisons, and systems that allow states to profit from housing female prisoners. Notably, those living in poverty are particularly at risk for incarceration, as they lack the financial resources to make cash bail or engage legal representation.

Dr. Brown-Dean made several important points during her presentation. Among them were the fact that in the United States, politicians have had a history of “addiction to punishment” and being “tough on crime, not smart on crime.” Dr. Brown-Dean firmly believes that the $200 billion dollar annual cost of keeping 8 million residents under criminal supervision should be reinvested in the community. Likewise, the $5 million being spent on each death penalty trial should instead be spent on victim empowerment. We also need to discard the practice of blaming victims of violence for their circumstances. According to Brown-Dean: “If we don’t stop making value judgments, there is no justice or freedom.” She also repeatedly emphasized the need for an intersectional perspective with regards to the criminal justice system.

Dr. Brown-Dean embraces the concept of authentic power: solutions should be offered by those who are closest to the problem. Also an advocate of helping women move “from pain to power”, Brown-Dean offers several pathways to reform. One such pathway is the elimination of cash bail. In addition, Brown-Dean would like to end the humiliation of menstruating, pregnant, and trans women. Furthermore, prior trauma needs to be adequately addressed, as 75% of incarcerated women have mental health challenges or have been victims of sexual and/or domestic violence.

Dr. Liat Ben-Moshe’s presentation referenced what Dean Spade and other scholars have termed a “queer of color” critique. Through the lens of disability, Dr. Ben-Moshe offers a “feminist crip of color critique” of incarceration; one which challenges traditional white liberal responses to and analyses of social problems, which incidentally are often dismissive of disability

Dr. Ben-Moshe’s analysis reveals that prison society affects everyone, not just those who are incarcerated and their families. Prison as a solution, along with similar alternatives like psychiatric confinement, shape the ways in which we interact with each other on a daily basis. Dr. Ben-Moshe reminded listeners that correction, reform, and rehabilitation have their roots in colonialism and forced assimilation.

Dr. Ben-Moshe also calls for increased focus on intersectional analysis. What is defined as a crime and who is labeled a criminal is a question that society needs to ask itself.

In her presentation, Dr. Ben-Moshe remarks on the toxic and invasive conditions to which prisoners are subject. She describes prisons as disabling. In addition, Ben-Moshe notes that a disproportionate number of prisoners come from impoverished backgrounds and that their environment makes them more likely to have a disability prior to imprisonment. Prisoners with disabilities are at a distinct disadvantage. Prisons typically do not provide accommodations like sign language interpreters for the deaf. Lack of accessibility to these much-needed accommodations means that prisoners with disabilities are often excluded from activities that expedite parole.

Dr. Ben-Moshe cites examples such as regular strip/cavity searches, poor ventilation in living areas, forced sterilization, and lack of access to quality healthcare as evidence to support her assertion that prisons are state-sanctioned violence. Dr. Ben-Moshe explains that prison reform is not the solution to prison violence. Building more humane or efficient prisons is not the solution. Dr. Ben-Moshe and other anti-carceral feminists would prefer that we change the focus from security. As she points out, “we need to treat harm, violence, and difference without incarceration.”

Dr. Lena Palacios agreed, noting that “instead of building prisons, we need to change the society that allows prisons to be a part of society.” In an acknowledgment of North Carolina’s settler colonialist history, Palacios began her presentation by listing the eight indigenous tribes who currently are recognized by the state of North Carolina and honored the rich legacy of the social justice movements who have challenged the injustices that have led to the carceral state.

Dr. Palacios calls upon folks to challenge the binary of innocent vs guilty, noting that too many people are limited by fear, shame, and trauma. She challenged the therapeutic model of redemption that is forced upon many prisoners. The prison system often perpetuates this shame, leading many to accept that the incarceration is an acceptable solution. Palacios describes the prison system as a “failure of imagination,” explaining that while (prison) abolitionism is a messy solution, it is one worth pursuing.

Borrowing a term from Dylan Rodriguez, Dr. Palacios refers to the “Prison Regime” that affects and disrupts the entire society, deforming everyone’s lives—not just those who have a personal relationship with someone who is incarcerated. In her own classroom, she encourages her students to realize, “We all have a connection to prison, even if it is not obvious”

Recognizing the fact that even academia has also been complicit in the re-narratization of trauma that to which prisoners are repeatedly subject, Dr. Palacios explored ways of questioning and addressing the violence and trauma of the prison system without recreating it. Dr. Palacios brought the panel to a conclusion, explaining that imagining a world without prisons may seem akin to science fiction, but there is no neat and simple alternative to the prison system.

Following the presentations, Dr. Brown-Dean, Dr. Ben-Moshe, and Dr. Palacios received questions from the audience, during which they elaborated on a number of topics raised during their talks. WGS graciously thanks panelists and attendees for an often uncomfortable but necessary enlightenment to the conditions that perpetuate the injustices of the carceral state.